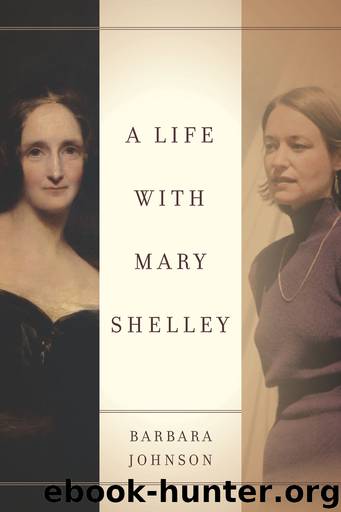

A Life with Mary Shelley by Johnson Barbara

Author:Johnson, Barbara [Johnson, Barbara]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2014-02-13T16:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER FOUR

Lord Byron

Byron was a commercial success and a famous figure in English Romanticism. But his fame as the “Byronic hero” was more biographical than textual, more mythical than literal. Here is how the Reader’s Encyclopedia describes it:

“Byronic hero”—a defiant, melancholy young man, brooding on some mysterious, unforgivable sin in his past. Whatever Byron’s sin was, he never told, but neither did he deny the legends of wildness, evil, and debauchery that grew up about his name.1

It is hard to see how this image could be derived from the poem that made him famous, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In fact, it is hard to see why that poem made him famous in the first place. It is a somewhat ironic version of the grand tour that young men of means were expected to make before their entry into life. The idea of a journey as a setting for tales was exploited by many previous authors, most notably Chaucer. The poem is written in Spenserian stanzas, and, like that author, Byron uses self-conscious archaisms. One new feature in this poem is that there are two heroes: Childe Harold and the general narrator. At first Childe Harold seems to be a narrative tool, and he is presented rather mockingly. But as more cantos are added, there seems to be a rivalry between the two for narrative primacy, and, in the end, Childe Harold drops out. The narrator calls him “the wandering outlaw of his own dark mind” (III.iii),2 but this characterizes neither Childe Harold nor the narrator, though it characterizes the Byronic hero they were both fighting to be.

Byron met Shelley at Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. Byron had just separated from his wife of only a year. He and Shelley were introduced by Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister, who had been Byron’s mistress in London and would soon give birth to his child. The two poets hit it off immediately and traveled to Chillon and Clarens together, leaving behind a jealous Mary, Claire, and John Polidori, Byron’s accompanying physician. Byron later settled in Venice, where Shelley joined him. When Shelley died in 1822, Byron considered himself responsible for his widow, and gave her many of his works from which to make fair copies. He himself died only two years after Shelley, of a fever in Missolonghi, where he had gone to fight for Greek independence.

Byron and Shelley had much in common. Yet they were also very different. They had both been bullied in school. They both loved to read. They were both unusually sensitive. Byron favored a kind of eighteenth-century mock-heroic style while Shelley wrote in a romantic lyrical style; Byron was a misogynist and hated feminists and bluestockings; Shelley promoted the rights of women. They had both lost their first loves and never got over it—Byron a neighbor and distant relative named Mary Chaworth and Shelley his cousin Harriet Grove; Byron learned his Calvinism and his sexual sensitivity from his nurse May Gray; for Shelley love was purely or primarily emotional.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12391)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7762)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5772)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5771)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5445)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5096)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4942)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4731)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4574)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4554)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4536)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4448)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4106)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4031)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4009)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3986)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3852)